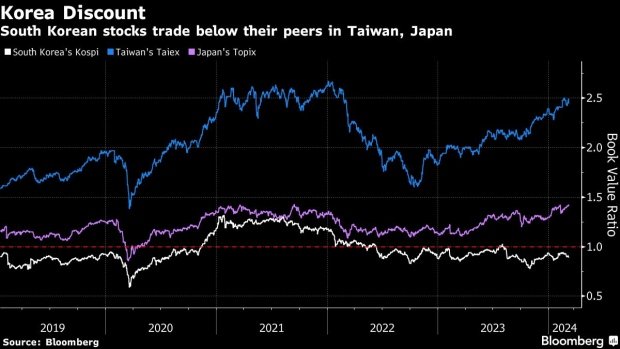

SK Hynix and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation are both leading Asian companies in different segments of the semiconductor industry having enjoyed similar annual sales growth rates of 10% and 14%, respectively, over the past decade. Yet, SK Hynix’s last five fiscal years’ median Price-to-Earnings (P/E) and Price-to-Book (P/B) ratios stood at 11.2x and 1.5x, versus 22.2x and 5.9x for TSMC.

This gap illustrates the general weaker P/E and P/B ratios of Korean listed companies compared to their international peers, a phenomenon dubbed “Korea Discount”. A research published in 2020 by the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, has quantified that the Korean stock market’s P/E ratio has been, on average, 30% lower over the 2002-2016 period compared to a group of 28 emerging and developed countries.

In 2022, approximately 61% of the Korea exchange market capitalization was comprised of companies affiliated with the top 30 family-owned groups defined by the Korean Fair Trade Commission. Therefore, it is impossible to explain the persistence of the Korea Discount without these groups called “Chaebols”. Two of their features particularly undermine equity valuations.

On the one hand, the capital allocation strategy of these groups is questionable and goes beyond the weakness of dividends and share buybacks that foreign investors frequently point out. Family-ruled corporations have maintained their diversification strategy, often towards unrelated businesses. This dispersion of capital doesn’t bring synergies while decreasing available funding for core activities, which still represented over half of these conglomerates’ total sales in 2018 according to an OECD report. When Chaebols don’t invest in new businesses, they tend to excessively hoard cash at the expense of investment, which is crucial to enhance growth prospects usually reflected by high P/E ratios.

On the other hand, the pyramidal structure of a chaebol and the system of circular shareholding between the group’s affiliates are detrimental to minority shareholders. This structure gives the ruling family greater control than their actual cash-flow rights would imply, encouraging them to conduct tunneling practices, i.e., diverting resources for their personal benefit or for the group’s interest at the expense of the affiliated company’s shareholder value.

The 2015 merger between Samsung affiliates Cheil and Samsung C&T is a case in point. The group’s founder’s grandson, Lee Jae-yong, who had a greater controlling stake in Cheil, was accused of rigging stock price to facilitate an acquisition of Samsung C&T at a discount price, thus expropriating Samsung C&T’s minority shareholders.

It is worth noting that cash accumulation, the multiplication of business lines or tunneling practices are further motivated by a top inheritance tax rate of 50%. In the latest example, the merger enabled Lee to prepare his upcoming succession to the Samsung group by taking control at a lower cost of the de facto holding company. Slashing this tax rate to the OECD average of 26% is subsequently essential, but also a prerequisite to gain the Chaebols’ cooperation on ambitious reforms.

These reforms can discipline the large groups’ capital policy in three ways. Firstly, the 2015 tax on accumulated earnings should be strengthened to limit unproductive cash holdings. Then, the Korean government could support a law compelling family-owned conglomerates to reduce the scope of their activities by ceding control of unrelated business. Lastly, conglomerates should be encouraged to issue guidelines that insist on the stability and frequency of dividend distribution more than their amount. Indeed, fully embracing a shareholder-oriented model that has proved to be inconsistent in fostering long-term growth is not a viable solution.

As for the promotion of minority shareholders’ rights within Chaebols, four measures can be considered. Improving the attractiveness of derivative suits filed by shareholders on behalf of the company deters controlling shareholders from committing tunneling practices detrimental to the affiliate business’s profitability. This implies increasing the benefits for plaintiff shareholder and attorney if they prevail and limiting litigation costs if they lose. Cumulative voting and electronic voting should also be made mandatory so that minority shareholder really exercise their rights. Policymakers should finally ensure a more active and independent role for the National Pension Fund, which is the main institutional investor of large companies, while further supporting domestic retail stock investment using dividend tax breaks on savings accounts. The ongoing rising number of retail investors will bring liquidity in the market and growing scrutiny of the public over the groups’ shareholder remuneration.

Yet, these reforms would be still insufficient since several studies underline that the Korea Discount also applies to non-Chaebol-affiliated firms. The Korea Discount issue should ultimately invite public authorities to tackle the broader challenges of the Korean economy. Notably, ensuring fairer competition between large and smaller businesses, as well as easing product market regulation and the barriers to foreign investment —both among the highest among OECD countries—would curb the Korea Discount for good.