Picture: Shenzhen (深圳), Guangdong province, China. Over the past decade, Shenzhen has emerged as China’s Silicon Valley and the leading hub in the manufacturing of smart devices used in AI solutions.

In my last article, I summarised the development of the Internet ecosystem and AI technologies in the United States and in China according to Kai Fu Lee’s essay. I will now delve into the “four waves” of the upcoming AI revolution that the author describes as well as its consequences on long-term growth, employment and Nation states’ power relations.

The Four waves of AI

Kai Fu Lee divides the commercial applications of deep learning AI algorithms into 4 consecutive waves: Internet AI, Business AI, Perception AI and Autonomous AI. Each one carries a more advanced version of AI than the previous one.

Internet AI

Internet AI is already widely spread in Internet, it powers all social networks, Web engine research and e-commerce sites we use. Internet AI is based on data labelling: a customer’s online activity generates data that is labelled, i.e associated with a specific result, which is a behaviour, such as “bought” vs “not bought”, “liked vs “not liked”. This labelled data feeds the AI which learns to know us better and better thanks to its neuronal structure. The deep learning algorithms subsequently improves dramatically the content suggestion for the user.

Internet AI lies behind the explosion of Internet giants’ profits, since it manages more than any other algorithm to propose us the product we desire or the ad that might catch our attention.

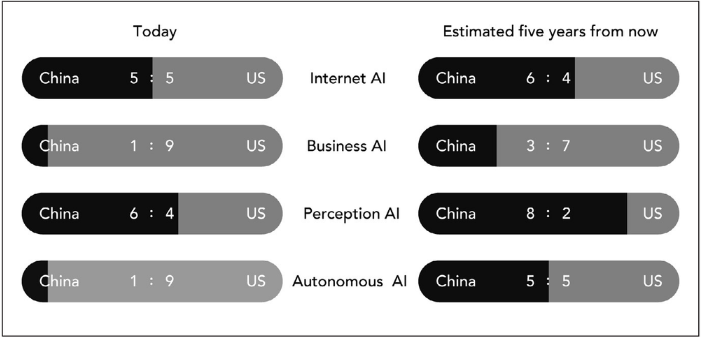

The United States and China have equal market share in this field, but the latter one may get ahead in the future thanks to its 700M of online active Internet users and highly digitalised consumption behaviours.

Business AI

It also relies on the use of labelled datasets to train deep learning algorithms, except this data is collected in older, traditional sectors of the economy.

The healthcare, banking and insurance industry have notably accumulated for decades vast amount of structured and organised data. A health record or a bank credit file is just hand-labelling data as they draw pattern between a set of factors (ex: general health indicators) and the occurence of a result (a disease). The commercial idea behind Business AI is to use this algorithm to predict with a better accuracy the occurence of a result by detecting correlation between minor factors and this result, patterns that the human brain cannot even realise.

As an example, a Chinese fintech company called Smart Finance was granting in 2017 2ml micro-loans with a 5% default rate, which is better than most retail traditional banks. No human is analysing the loan applicant’s file, but an AI algorithm that asks the user a broad access to its personal information, where it finds hidden correlations with default risk (ex: the speed at which it filled its personal information on the app, his phone’s average level of charge).

Business AI is the only field of this technology application where the US will still lead over China, because China lacks comprehensive and standardised datasets in “the old economy’s” sectors.

Perpective AI

It marks one step further in the blurring between digital and real worlds. Indeed, this type of AI is deemed “perceptive” by Kai Fu Lee because it now sees, hears and feels the real world the same way the human being does using his senses. How?

A perceptive AI is “fed” by information about the real world through smart devices (sensors, cameras…), it digitalises the physical world, i.e translates it into numerical data that are then used to train this algorithm so that it can improve the execution of of a service in the physical world. The efficiency of perceptive AI relies on the multiplication of smart devices that act as bridges between physical and digital world and gives eyes and ears to the algorithm. At the same time, it blurs the frontier between these two worlds.

For example, when someone asks to its home assistant (a kind of advanced Alexa) to order for him food for delivery using his phone connected to the assistant, can we consider that he is in the real world or on the Internet?

Perceptive AI has extremely widespread applications: real-time traffic regulation using smart cameras, payment using face recognition, automatic translation, personalised education services… It relies always on the existence of smart hardware which gives born to Internet of Things (IoT), a field where China excels which gives it a considerable edge over the United States. Indeed, China leads in the production of intelligent cameras and drones with the Chinese drone manufacturer DJI capturing over 50% market share worldwide, US included.

Autonomous AI

Once the AI will have eyes and ears to feel the world the same way we do, it won’t last long before it can move autonomously in this world. The most important AI wave – but distant in the future – will take the form of what we generally called robots, i.e a machine powered by AI and being able to replicate up to a certain limit human movements.

Autonomous AI-powered robots will be deployed where they can replace human movement with a better efficiency, i.e commercial spaces: farming fields, warehouses, factories. Some production process are already automatised but none of them are autonomous, i.e so far these machines can only perform repetitive tasks and they can’t make movement decisions based on the environment’s sensorial analysis.

Autonomous AI will also shake up transportation, with the advent of Level 5 Autonomous Driving Systems (ADS). In this field again, The United States (Alphabet-funded Waymo ADS and Tesla) and China (Baidu) dominate, with China expected to catch up with the United States quickly.

China and US’ market shares in the AI applications as of 2018.

AI’s devastating effects on social and economic structures

Kai Fu Lee points out the fact that policymakers and economists in the US and in China underscores the fallout of AI on employment and inequalities. According to him, AI will trigger a massive and rapid suppression of jobs and will accentuate inequalities, at the same time productivity gains will soar.

Kai Fu Lee explains that any comparison with past technologies is misleading. AI, with steam machine, electricity and the new technology of information and communication (NTIC) are the Humanity’s four general-purpose innovations, i.e the only that have shaken up the whole socio-economic structure.

The first two innovations have triggered the Two Industrial Revolutions (1760-1830 and 1870-1914). These period of great change saw formerly qualified workers losing their job because innovation led to the division of one occupation into several smaller tasks that initially didn’t need strong qualifications. That is the example of manual weavers being outcompeted by low-skilled rural migrants working with steam-powered weaving machines. However in the long-term these innovations have brought about huge creation of new jobs and increase of average income. The NTIC revolution also boosted productivity factor but brought about the creation of highly qualified, high paid jobs (developer) and low qualified and paid jobs (UberEat deliver). It has resulted in the stagnation of median incomes in developed countries. Even if soaring inequalities in the West may be due to other factors (de-industrialisation…), the positive correlation between innovation and the long-term increase of median income claimed by techno-optimists is not systematic.

The AI revolution will not only further increase inequalities (A), it will also entail net job destruction (B)

A) The increase in inequalities will be systematic, both within societies and between countries. Because of the network effect of a data-based business model (more data => the service gets better), the first companies that are pioneer in a given AI application will likely stay the first and will consolidate their position over time, reaching a monopoly or near-monopoly situation. Monopolies traditionally goes with higher wealth inequalities. Meanwhile, AI will benefit wages of a relative small of non-replaceable numbers workers while pushing down replaceable workers’ wages, mechanically increasing inequalities.

AI will also durably generate a new hierarchy. At the top, the United States and China, which according to PwC will capture 70% of the AI market by 2030 and with this most of the productivity gains associated with AI. Then comes the handful of countries that will capture the remaining 30% because of their hardware manufacturing capabilities or the existence of an autonomous Internet ecosystem. They are mainly Asian countries : India, South Korea, Singapore, Russia….. It is not sure whether Europe will fall in this group or not. The most unfortunate will be populous developing that didn’t have the time to build wealth by implementing the Asian-like export-led industrialisation model.

B) Kai Fu Lee gives a upper-hand estimation of job losses arising from AI. He compares the long-commented studies of Frey & Osborne (2013), the OECD (2016) and PwC (2017) and his findings are closed to the latter one : by 2030, around 40% of American jobs could be automatised by AI applications. He notes that most analysts neglect the speed of diffusion of replicable algorithm, which makes the adaptation through re-qualification insufficient and the studies outdated. Kai Fu Lee’s final rate of replaceable jobs tops 50% as he adds 10% of potential job cuts due to AI’s indirect impact on jobs that are not directly replaced but exposed to entirely new, AI-funded rival business models. These potential job losses, partly offset by job creations ( data scientist…) will result in a permanent unemployment rate of 10 to 25%.

Kai Fu Lee finds similar findings for China, except the job market will be shaken up more slowly, by step. Indeed, China has a higher share of GDP generated by industry. AI applications targeting manufacturing jobs won’t roll out soon due to the technical complications of building robots. As highlighted by the Moravec paradox It is easier to commercialise algorithms replicating the intellectual skills of adults than smart robots imitating mobility abilities of a 6-year-old child.

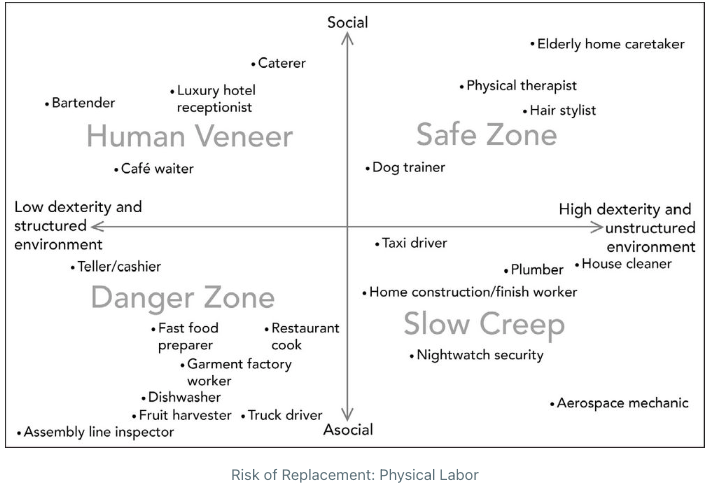

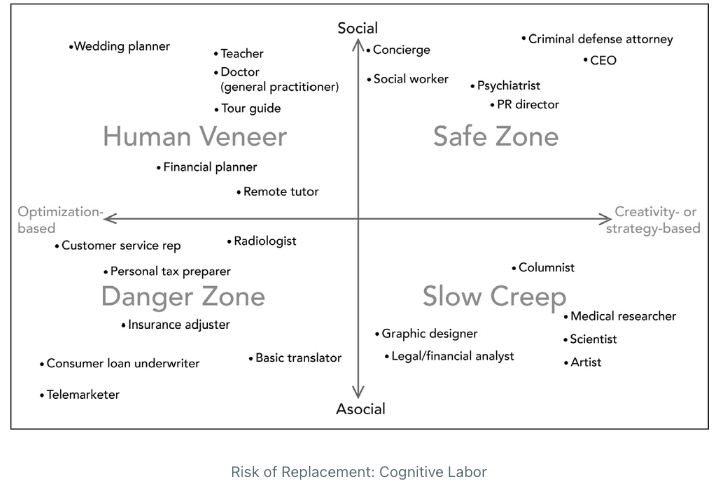

This relates to Kai Fu Lee’s last observation about the nature of suppressed jobs. This time, white-collar collars will be just as affected, if not more by AI than blue-collar jobs. The association white-collar job => qualified job / blue-collar job => non-qualified job is short-lived. For both cognitive and physical occupations, Kai Fu Lee defines four groups more or less exposed to automation.

Solutions and Conclusion

Kai Fu Lee opposes universal basic income, which he sees as a purely individualistic measure supported by Silicon Valley executives because it allows them to avoid confronting the consequences of their innovations and economic model.

Re-qualification is important in his opinion, and the reduction in working hours to share reduced jobs between the population can be considered, but both don’t represent a comprehensive solution to the problem.

Though the path towards economic adaptation will be long, Kai Fu Lee remarks that most of the jobs, notably “Human veneer” and “Slow creep” groups can co-exist with AI. As an example, business AI will soon be able to deliver more accurate medical diagnosis by analysis thousands of past similar cases with symptoms similar to the addressed patient. However, no one wants to be dealing with an AI only during medical inspection, a human presence will always be needed.